The Impact of a Single Stretching Session on Running Performance and Running Economy: A Scoping Review

Overview

Controversies have been around the different techniques of stretching when acutely applied prior to a running event. To the best of our knowledge, this review is the only one to assess the current evidence regarding the effect of these techniques on either Running Performance or Running Economy.

This study aims to investigate the different stretching techniques and durations since no review has comprehensively reported the effects of a single bout of stretching, with variations in duration and technique, on running performance and/or RE.

Introduction

Running Economy (RE) is a key physiological determinant for performance, measured by steady-state oxygen consumption at a given speed. Running involves complex interactions of muscle–tendon units, which adapt to chronic stress. Stiffer tendons of the plantar flexors and stiffer muscle–tendon groups of the hamstrings also enhance RE in which is crucial for performance and can be achieved through both long-term and acute interventions. Long term interventions (≥8 weeks), including resistance training and plyometrics which are recommended for endurance athletes. While acute interventions are often performed during the athletes warm up to improve the running performance (i.e. distance, stride length) and RE.

Study Parameters

Upon doing a search hit study, a total of 1043 studies were found. Only the studies that were related to Running Performance variables and RE were selected to evaluate their effects from a single bout of acute stretching, ending up with 11 studies for analysis in this review. Ninety-nine male runners (middle, distance and recreational runners) and 12 female distance runners with an average age of 25.3 years were included.

Results

Static Stretching

- The duration of static stretching’s involved in the reviewed studies were up to 10 minutes per muscle–tendon unit.

- Running performance and RE were more impaired by longer stretching durations (≥120 seconds) decreasing muscle stiffness potentially impacting muscle performance compared to shorter ones (≤90 seconds).

- Static stretching (3-4 x 30 seconds) of the lower body was found to reduce running performance suggesting an increased ground contact time and decreased efficiency in energy transfer in males. (Lowery et al and Wilson et al)

- Damasceno et al. reported decreased jump height and a slower first 100 m in the 3-km run in the stretching condition without impacting the run performance and RE, suggesting neuromuscular impairment from static stretching.

- Stretching plantar flexors or hamstrings for more than 60 seconds reduces muscle–tendon unit stiffness, potentially having a detrimental effect on running performance/economy by increasing ground contact time

- Less flexible individuals may achieve beneficial flexibility through stretching, improving RE.

- However, in females no significant differences between the static stretching and non-stretching conditions in running economy (RE), calorie expenditure, heart rate, and endurance performance. Speculated that the discrepancy in results between male and female runners could be due to less stiff muscle-tendon units in females.

Dynamic Stretching:

- It’s not possible to quantify and detect the duration of the stretching of a single isolated muscle group due to the complex movement associated with dynamic stretching.

- A significant improvement in running performance (9.8%) was observed with prolonged time to exhaustion and running distance in the dynamic stretching group. (Yamaguchi et al.). An average impairment in RE was found.

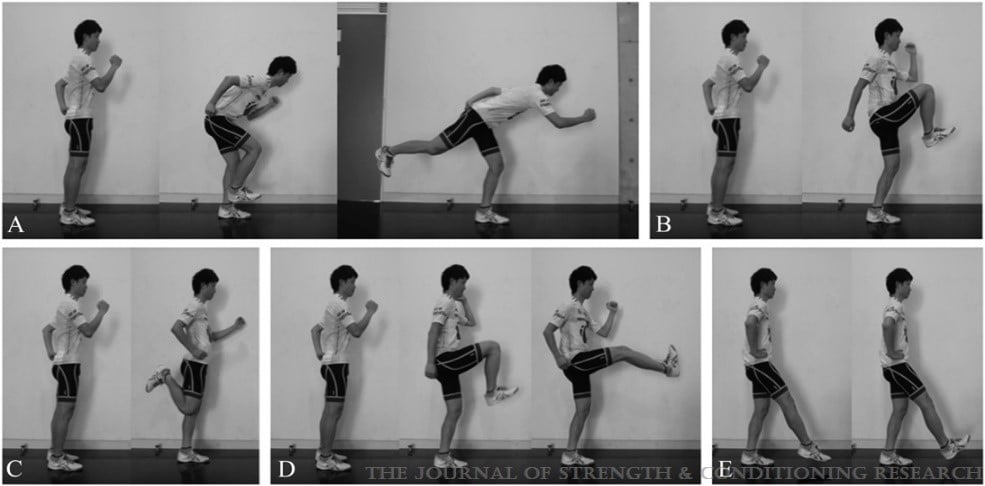

Figure 1 Examples of different dynamic stretching (Yamaguchi et al, 2015, p. 3047)

Figure 1 above displays the examples of dynamic stretching as in the following order: (a). hip flexion with posterior extension of his leg. (b) Hip flexion with knee raises towards the chest (c) leg extensors with knees flexed to buttock (d) Leg flexors with thighs parallel to the ground and knee bent at 90°, then subject contracts the quadriceps to extend the knee, bringing the leg forward in front of his body (e) plantar flexors and dorsiflexion of the ankle joint

- Zourdos et al. found no differences in running performance after dynamic stretching and observed increased energy expenditure (impaired RE) after dynamic stretching compared to non-stretching.

- Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation (PNF) stretching of the quadriceps muscles before running might help improve running performance/economy by decreasing tendon stiffness.

Post-stretching dynamic activities:

Performing dynamic activities after static and dynamic stretching exercises for up to 90 seconds in the warm regimes (i.e., vertical/countermovement jump height or 20-m sprint). can have a positive effect on springiness performance. While longer than 120 seconds can be detrimental.

So ultimately, the inclusion of some dynamic activity after stretching seems to counterbalance adverse effects and enhance performance especially with shorter stretching times.

Conclusions and Real World Application

Static Stretching is not recommended for healthy athletes with normal flexibility to apply static stretches for 60 seconds or more prior to running events when aiming to improve RE or performance and longer durations can have detrimental impacts, particularly in normally flexible athletes.

While static stretching may not improve running performance, it has been associated with a 54% reduction in acute muscle injuries.

Short-duration dynamic stretching is recommended for increasing running performance, particularly when performed for short durations (up to 220 seconds) without further warm-up. For example: Bent – knee forward swings, straight-lateral swing and side lunges.

Implementing post-stretching dynamic activities is likely to decrease the likelihood of performance deficits. For example: applying a 20m sprint after the stretches.

Targeted stretching of muscle groups for which greater compliance is beneficial for RE (e.g., quadriceps muscles).

Limitations of the Study

The quality of the data collected may be prone to bias or inconsistencies as the analysis relies on previously collected data that was not originally intended for the current study which may compromise its validity. There is an imbalance gap in gender ratio (99 males – 12 females). The Duration of dynamic stretching is hard to quantify as it is associated with an overall body movement and only can be detected in static stretches since it is involved with activation of isolated muscle group.

Further Research Needed

More studies are needed to investigate the effects of stretching on participants with different flexibility levels to better understand group responses to stretching on RE and running performance.

More studies on female runners are recommended to better understand the gender-specific impacts of stretching.

Further investigation into the effects of isolated quadriceps stretching before running events is needed to determine potential benefits.

Post-stretching dynamic activities appear to mitigate the negative effects of stretching and improve performance, particularly when shorter stretching durations are used. Future research should focus on combining stretching with dynamic activities to further understand their impact on athletic performance