Heart rate is a common metric used by endurance athletes to measure training effort, but is it always the best measure and for every type of athlete? We break it down for you.

Heart rate is used by many endurance athletes as a way to both assess and prescribe workout intensities. While heart rate is fine to use as a training metric in some cases, two reasons often cited where it falls short is in regard to heat and cardiac drift. Heat is pretty obvious – the higher the heat, the higher the heart rate response. Cardiac drift refers to the heart rate continuing to elevate even though the exercise intensity stays the same.

However, there is one case that is not mentioned that much… but it should be. This has to do with individuals that are deconditioned. This is important for both athletes, as well as coaches.

It is common knowledge that a lowering of one’s heart rate is a physiological adaptation of becoming more fit from a cardiovascular standpoint. This has to do with the heart’s efficiency. Meaning, as one becomes more fit, more blood is ejected out of the heart with each pump (i.e., stroke volume), therefore, less ‘pumps’ are necessary… which is why one’s heart rate is lower.

Conversely, deconditioned individuals often have high heart rates – at rest, during normal activities and during exercise. This is due to the heart’s inefficiency and thus, requiring more pumps to supply the same amount of blood as compared to that of a trained individual.

Heart Rate / Perceived Exertion Mismatch

By most accounts, a heart rate of 160 bpm is fairly high and likely above ones lactate threshold (LT). Meaning, for a well-conditioned individual, this heart rate would represent a pretty intense effort.

However, for someone that is substantially deconditioned, their heart rate might shoot up to 160 or above with minimal physical effort and as such, their perceived intensity may be quite low.

Huh?

To the uninformed, being able to exercise at 160 bpm with little to no exertion might seem like the domain of the elite athlete. However, aside from this being at odds with each other from a physiological standpoint, the real tell tale sign is the speed at which the athlete is moving… likely quite slow.

To The Moon!

Intensity and heart rate typically increase linearly. However, this only holds true for someone in good aerobic shape.

CASE STUDY

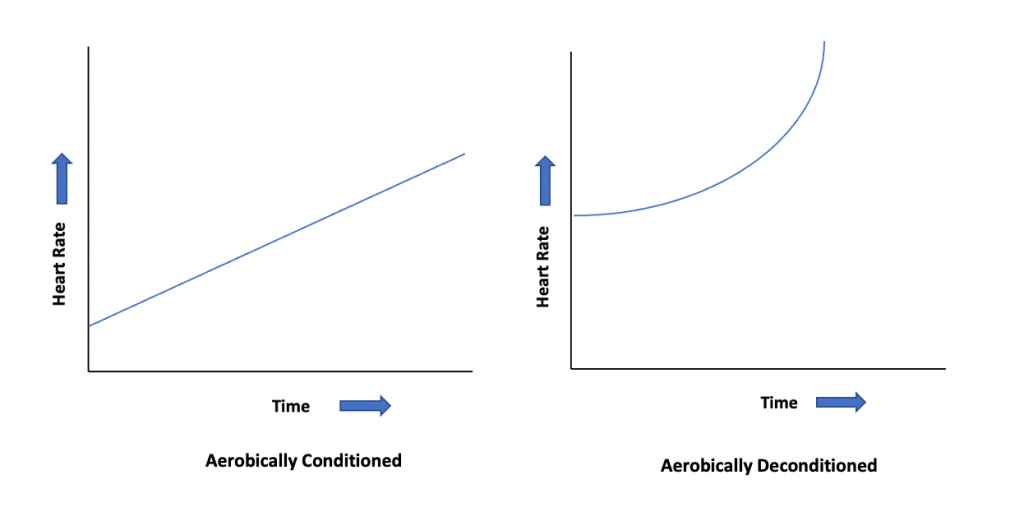

The below charts demonstrate the mismatch of heart rate and exertion for a decondtioned individual. For these two hypothetical individuals, they were both instructed to warm up on a bike for 10 minutes at an easy pace and then gradually increase their exertion level every minute. The blue lines represent perceived exertion level.

For starters, you can see that the deconditioned athlete starts out at a much higher heart rate than the conditioned athlete, even though they are at similar exertion levels.

The well conditioned athlete sees their heart rate increase in a linear fashion to their exertion level. However, the deconditioned athlete doesn’t see much increase in their exertion level initially, but not long after starting, their heart rate and exertion skyrockets upwards in a curvilinear pattern... let’s hope not to the moon! This athlete would likely be unable to continue much longer due to exhaustion.

Perceived Exertion / Lactate Threshold Mismatch

As noted above, it is not ‘normal’ for an individual to be able to easily exercise at 160 bpm. One’s ventilatory threshold (VT), or when breathing starts to become labored, is highly correlated to one’s lactate threshold (LT). This is why using the Talk Test assessment as a way to benchmark one’s LT is very useful. However, there is one caveat. This assumes that an individual is in fairly good aerobic condition.

While it is normal that an athlete’s VT/LT is 160 bpm, this would coincide with labored breathing. However, with a deconditioned individual, their breathing and effort level may not be elevated much at all. In respect to one’s VT and thus LT, this would seem to signify that the individual has not reached their LT.

One of the major benchmarks for physical improvement in a training program is the increase in one’s LT. Therefore, in the case of the individual noted above, from purely a quantitative standpoint, it may appear that they are in great shape… seeing as how they are breathing easily at 160 bpm and thus, signifying that they have not yet reached their LT. This of course is not the case.

Opposite Directions

As discussed above, for an in-shape athlete, their breathing rate (VT) is correlated with their heart rate – easier = lower heart rate, harder = higher heart rate. However, as a deconditioned individual gets more aerobically fit, they will see their VT (or the point at which their breathing becomes labored) decrease in relation to their heart rate. Again, purely from a quantitive standpoint, this may appear that the deconditioned athlete is actually getting more out of shape. However, the opposite is actually true as it is a result of the heart increasing in stroke volume and decreasing in stroke rate. This typically correlated with being able to run/swim/bike at the same or faster rate with the same or lower heart rate.

What To Do?

If an individual is substantially deconditioned, it is advised to not use heart rate as a metric to prescribe intensity. Instead, focus on perceived exertion. There are many physiological adaptations that occur at low intensities that relate to the development of one’s aerobic conditioning. Therefore, have the individual exercise at an intensity that seems fairly easy and look for their heart rate to decrease over time, while exercising at the same intensity level.

If an individual was in good aerobic condition fairly recently and knows at about what heart rate their VT was at, you can shoot for that as a goal. For example, if they can currently exercise at 160 bpm with barely any perceived exertion but they know that previously their VT/LT was around 140 bpm, a good strategy would be to keep the intensity and exertion low until their VT is around 150, at which point adding some intensity to the program to further develop their aerobic capacity would be a good idea.

However, if an individual is new to exercising and therefore they don’t have any past data to benchmark off of, keeping the intensity and exertion low for a while to see how their heart rate responds would be recommended. One thing to note, as there are environmental factors (i.e., heat) and other variables that influence heart rate, from the perspective of benchmarking progress using heart rate and exertion, keeping things as constant as possible (route, exertion, speed) is advised.