Ah yes, iliotibial band syndrome, or ITB Syndrome (ITBS) for short. If you’ve been a runner or cyclist for even a day or two, you’ve likely heard of this term and it being synonymous with pain at the side of the knee.

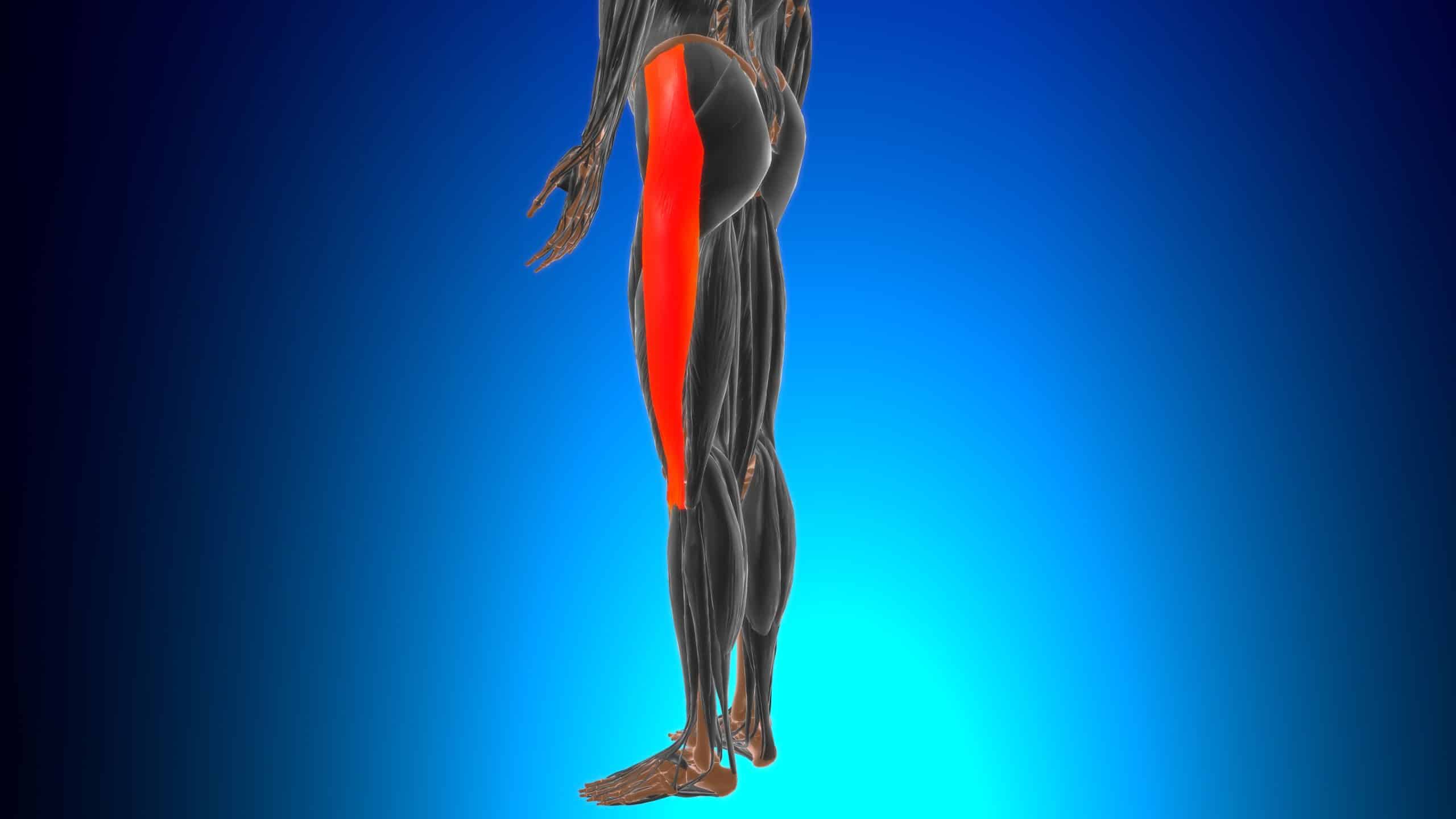

Before we go any further, let’s define what the IT Band is. The IT band (or tract) is a thick band of connective tissue (fascia) that originates at the top of the pelvic crest and inserts on the lateral head (lateral condyle) of the tibia, right below the knee. It runs down the lateral side of the thigh. In respect to running and cycling, the primary role of the ITB is to stabilize the knee.

Friction Syndrome?

Due to where the ITB inserts on the tibia, pain at the side of knee while running or cycling has traditionally been thought to be caused by the ITB rubbing against the protrusion on lateral side of the femur where it meets the knee, essentially a shearing-type movement. This bony protrusion is called the lateral femoral epicondyle. This is why ITBS is also commonly termed, ‘IT Band Friction Syndrome (ITBFS).’

The ITBFS theory largely assumes that there is a bursa sac between the ITB and the lateral femoral epicondyle. A bursa sac is a fluid-filled sac whose purpose is to reduce friction between surfaces. ITBFS is therefore theorized to be the result of inflammation of the bursa sac (bursitis).

However, research by Fairclough et al., found no presence of a bursa sac between the ITB and lateral femoral epicondyle. What was found was a layer of high innervated fat (i.e., lots of nerves) below the ITB… more on this later.

Movement of the IT Band

ITBFS is thought to be caused by the ITB passing, or rolling over the lateral femoral condyle in a front to back motion when the knee bends… therefore causing friction.

The same study by Fairclough et al., also found that the ITB is firmly anchored to the femur and is also part of the tensor fascia lata (TFL) and thus, the theory that it ‘passes over’ the lateral femoral epicondyle is incorrect.

Compression

In the Fairclough study, two runners that presented with ITBS showed no changes in the ITB based on magnetic resonance scans in relation to asymptomatic runners, but changes in the fatty layer under the ITB were identified. It was also discovered in the study that the ITB compressed against the lateral femoral epicondyle at 30-degrees of knee flexion. This was largely due to internal rotation of the tibia. Therefore, ITB pain is most likely due to compression of the fat layer beneath the ITB versus friction caused by the ITB ‘rolling over’ the lateral femoral epicondyle. In other words, the ITB or bursa sac (which is not present) is not what is irritated, it’s the fat layer underneath it.

Training Implication

Like most running and cycling-related pain, the common advice and treatment options for ITBS typically revolve around stretching and foam rolling.

Let’s first address stretching. The ITB is a very tough structure. In fact, in a 2010 study by Falvey et al., a strain gauge was used to test various stretches on the ITB and the result was that the ITB was unaffected.

Therefore, it is highly unlikely that stretching will have any effect on the ‘tightness’ of the ITB.

Now let’s discuss foam rolling. This is pretty simple. Stop doing it! Anyone that has ever performed foam rolling on their ITB will tell you that it is insanely painful. The erroneous and commonly held belief is that if it’s painful, it must be tight and therefore more foam rolling is the answer. However, let’s refer back to what is likely the cause of ITB pain – compression. Assuming this is true, or at least a very strong contributing factor, common sense would dictate that adding compression via foam rolling will only exacerbate the issue.

Recommended Course of Action

So, what should one do if they have pain at the side of the knee? As ITBS is largely an overuse injury, the first logical step would be to rest or at the very least, reduce training volume. Like a lot of other pain-related issues, the localized area of ITBS pain is likely the result of dysfunction in one or more areas. In the case of ITBS, according to Fairclough et al., it is likely that hip dysfunction may be a leading cause. Therefore, seeking out a trained clinician is likely the correct course of action.

REFERENCES:

John Fairclough, Koji Hayashi, Hechmi Toumi, Kathleen Lyons, Graeme Bydder, Nicola Phillips,5 Thomas M Best, and Mike Benjamin. “The functional anatomy of the iliotibial band during flexion and extension of the knee: implications for understanding iliotibial band syndrome”. J Anat. 2006 Mar; 208(3): 309–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00531.x. PMCID: PMC2100245. PMID: 16533314

Falvey EC, Clark RA, Franklyn-Miller A, et al. “Iliotibial band syndrome: an examination of the evidence behind a number of treatment options.” Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010 Aug;20(4):580–7. PubMed #19706004

Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H, et al. Is iliotibial band syndrome really a friction syndrome?. J Sci Med Sport. 2007;10(2):74-78. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2006.05.017

_____________________________________________________________________________

Rick Prince is the founder/director of United Endurance Sports Coaching Academy (UESCA), a science-based endurance sports education company. UESCA educates and certifies running and triathlon coaches (cycling and ultrarunning coming soon!) worldwide on a 100% online platform.

Click here to download the UESCA Triathlon Course Overview/Syllabus

Click here to download the UESCA Running Course Overview/Syllabus