Running a successful marathon is not just about training and endurance, you also need to be on top of some very important racing strategies and keys. We cover 3 important strategies that are a must.

Having a successful marathon takes a winning strategy and some key planning.

To help your clients be marathon race ready, make sure to include winning strategies for pacing, hydration and course preparation for the marathon distance (26.2 miles). Whether you are coaching an experienced runner or an athlete looking to complete their first long distance running event, there is bound to be a tip or two you can take away.

Winning Strategy #1 – Pacing

Regardless of experience, pacing during the event will be a key factor in hitting a goal time or reaching the finish line. Pacing can be the difference between finishing strong and dropping out. During the months leading up to the event is the time to develop a pacing strategy through time trials and long runs. Practicing pacing discourages two big mistakes: Going out too fast and therefore risking blowing up, and: Going out too slow and risking missing the targeted time.

Here are three keys to consider when determining a pacing strategy for a marathon:

- Race pace is determined during training and based on assessments of an athlete’s fitness level. Correlating an athlete’s effort level, such as lactate threshold, to assessment methods (i.e., heart rate, power, RPE, etc.), will enable the athlete to track their pace throughout an event.

- Smooth and steady is a better pacing option than erratic and punchy. To ensure a steady effort, take into consideration the event terrain and adjust by focusing on running at a steady effort rather than a constant pace.

- Stick to the script. It is important to adhere to the pre-planned race pace strategy, especially at the beginning of the race when it’s tempting to go out too fast.

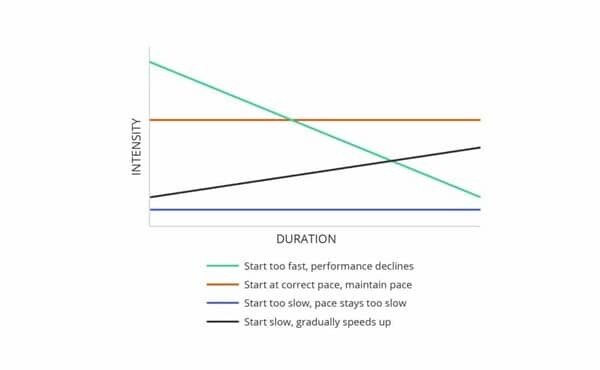

The image below shows various pacing strategies. Of the four strategies, only the orange and black are recommended.

For more in-depth information on pacing strategies, and additional resources and tools, check out this post Risk Based Pacing (Part One)

Winning Strategy #2 – Hydration

To prevent dehydration that can impair performance, have a reliable marathon hydration strategy for your client.

Hydration is a heavily debated topic, primarily in the world of athletics. There are two primary schools of thought regarding proper hydration strategy and guidelines. We’ll take a look at both along with potential shortfalls, as it is likely that the “correct” strategy lies somewhere between the two. Presenting both strategies/guidelines enables you as the coach to determine what works best for your clients.

Hydration Strategy #1

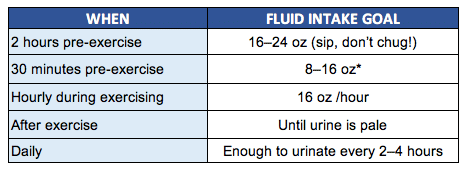

The most adhered to drinking strategy is to drink before feeling thirsty. The thought process behind this is that if you wait to drink until you are thirsty, you are likely already dehydrated to some degree. This strategy typically involves a predetermined hydration strategy, including drinking prior to exercising, with set amounts of fluids being consumed at predetermined intervals during exercise. The chart below illustrates such a strategy:

Hydration Strategy #2

This strategy is based on research by Dr. Tim Noakes, a sports science professor at the University of Cape Town, who has challenged the norm regarding hydration. Dr. Noakes is the author of Waterlogged: The Serious Problem of Overhydration in Endurance Sports. In this book, Dr. Noakes looks to debunk what he considers myths regarding hydration in respect to endurance events. His primary point of contention with the accepted school of thought regarding hydration is that there is no preset amount of fluid that needs to be taken in before or during athletics events. Rather, Dr. Noakes states that thirst is the body’s self-regulation system to tell it when it needs fluids. In other words, drink only when thirsty.

Below are the points that Dr. Noakes makes regarding hydration based on his studies:

1 – Mild dehydration does not result in heat exhaustion or other health issues.

* Mild dehydration does increase the perception of effort.

2 – Mild dehydration does not increase core temperature to dangerous levels. An increase in core temperature is most correlated to an increase in intensity.

3 – Collapsing at the end of endurance events is rarely the result of dehydration or high body temperature (hyperthermia). Rather the cause is typically the result of exercise-associated postural hypotension (EAPH) that is caused by a rapid fall in blood pressure. This is most often due to blood pooling in the feet and therefore a lack of blood flow to the brain.

4 – Hyponatremia is primarily caused by overconsumption of fluids versus an underconsumption of sodium.

5 – Drink only when thirsty.

6 – Drinking when thirsty is just as effective in controlling sweat loss as drinking set amounts at set intervals.

7 – Change in body weight is only one variable when determining sweat loss.

8 – Drinking more fluids than what is required to quench thirst does not increase performance.

Of the above points, here are two potential shortfalls:

- Even if mild dehydration has no impact on one’s health, if mild dehydration increases one’s perception of effort, this will likely negatively impact performance.

- Drinking when thirsty versus drinking preset amounts is reliant upon an individual being in tune with the body. For many athletes, the thrill and excitement of competition blurs other aspects of an event. In respect to hydration, oftentimes athletes are so focused on other aspects of the event that they “forget” to drink and eat. This may result in individuals drinking when they are quite thirsty and thus drinking more than they would have when they were initially thirsty. Taking in large amounts of fluids while running may cause stomach cramps, which in turn reduce one’s performance.

Therefore, assuming that drinking when thirsty is the correct strategy, as a coach you must be confident that your client has the focus and body awareness to do so during competition.

Hydration Conclusions

While it is easy to adopt a singular hydration strategy, the correct strategy is likely a hybrid of both the aforementioned strategies, and to Dr. Noakes’s point, the right strategy is likely based on an individual versus a pre-formatted strategy or “rule.”

Winning Strategy #3 – Race Course Knowledge

The final winning strategy for racing the marathon is awareness of the race course. Here are examples of what an athlete (and coach) need to know:

- At what mile markers the aid and hydration stations will be

- The elevation profile (notable climbs or descents)

- Type of terrain (i.e., completely road or mixed with off-road terrain)

Besides the information that is provided by the race director (on the event website), other great sources for this type of information is online message boards and forums, and pre-race informational sessions.

If possible, drive the race course in advance for a better sense of elevation, landmarks and turns.

Summary

Having a successful race day means having a proper plan in place. While not an exhaustive list, be sure that ample time has been devoted to creating a pacing strategy that will ensure the best possible result; establishing a well-practiced hydration plan to safely prevent dehydration; and ensure you and your client are well familiar with the race course, both for preparation and race day success. Winning strategies make for successful races!

Sean Begley is an advisor and contributor to United Endurance Sports Coaching Academy (UESCA), a science-based endurance sports education company. UESCA educates and certifies running, ultrarunning and triathlon coaches (cycling and nutrition coming soon!) worldwide on a 100% online platform.