Strength training and strength training for endurance athletes are not exactly the same thing. There are many considerations to take into account for endurance athletes. We cover them here.

The History

Ahh yes, strength training – the nemesis of any endurance athlete… or at least that is what we are often led to believe. For starters, despite being debunked many many years ago, the myth that lifting a weight or doing a lunge will automatically add pounds of muscle still persists to this day. And as many endurance athletes are concerned about their weight, this myth often precludes any sort of strength training for those that buy into this myth. Additionally, as training for a lot of endurance events takes quite a bit of time, it’s easy for endurance athletes to dismiss strength training as a ‘if I have time for it’ sort of thing.

As a result of these factors and likely many more, at best, strength training has historically had an acrimonious relationship with endurance sports.

Regarding the ‘I’ll bulk up’ myth, a 2015 study by Beattie et al. found that over a 40-week period, distance runners who participated in a strength-training program were able to improve their leg strength while not adding any “unwanted” muscle mass. It is proposed that this adaptation is largely due to improved neuromuscular function (11).

The Physiology

There are two main areas of physiology and exercise science that pertain to strength training.

Overload Principle

Benefits reaped from strength training are the result of the overload principle. The overload principle states that a greater-than-normal stress on the body needs to be present for a training adaptation to occur (1). The overload principle was developed by Thomas Delorme, M.D., who used heavy-resistance training exercises on soldiers who had just returned from WWII. Rapid rehabilitation of soldiers was necessary as there was a shortage of hospital beds at that time. In 1951, Dr. Delorme and Arthur Watkins published their findings in a book called Progressive Resistance Exercises (2).

While the overload principle originated from a resistance-training perspective, all training adaptations are based on this principle. Regarding strength training, the overload principle can relate to different physiological adaptations, such as muscular endurance or power.

Neuroendocrine Response

An area rarely discussed regarding strength training is the neuroendocrine response. This response refers to the interactions between the nervous and endocrine systems that occur when performing specific types of strength-training movements. The greatest neuroendocrine response occurs when performing exercises that recruit large muscle masses and are done at a relative high volume with moderate to high resistance (3, 4). This response increases testosterone and hormones (i.e., growth hormone) that stimulate muscle growth/strength.

Testosterone is a hormone within the body responsible for muscle growth (5). Testosterone is a steroid hormone from the androgen group that is responsible for protein synthesis (6). Therefore, testosterone is responsible for an increase in muscle size/strength, hair growth, and bone density. In males, testosterone is secreted by the testes, and it is secreted by the ovaries in females. Additionally, a very small amount of testosterone is secreted by the adrenal glands. Adult males produce approximately seven to eight times more testosterone than females (7).

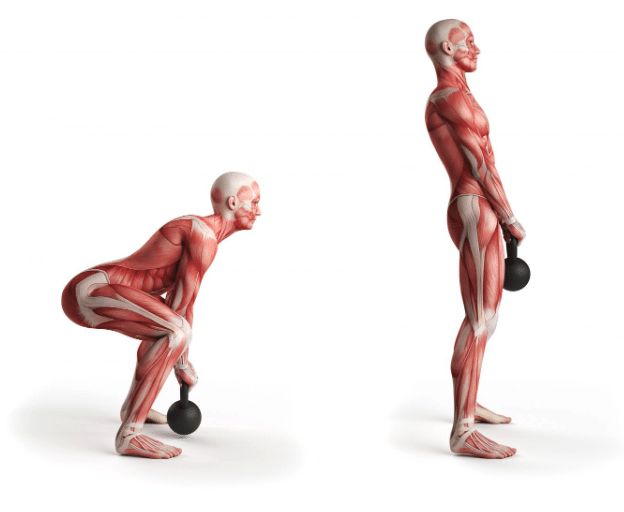

While the strength program of an endurance athlete won’t contain high neuroendocrine response exercises exclusively, it is of crucial importance to include them in a program. Exercises that have a high degree of neuroendocrine response are those that incorporate multiple large-muscle groups such as the squat, dead lift, and other Olympic-style lift exercises (5).

The neuroendocrine response also influences the order in which exercises should be completed. Exercises that have a high neuroendocrine response increase, for a short time, the amount of testosterone circulating in the blood. Therefore, performing exercises that do not elicit a high neuroendocrine response (e.g., shoulder raise) should typically be done after exercises that do have a large response. These smaller muscles (low neuroendocrine response) will be able to reap some of the benefits of the response because of the increase in testosterone in the bloodstream.

Energy Expenditure

There is no question about it, strength training is advantageous for endurance athletes. However, it is important to note that its importance in terms of its benefits is not equally spread across all endurance sports or all disciplines within a particular sport. For example, both 5K and 100 mile races are running events, but at opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of physiology and other demands – specifically training time.

Training for an ultramarathon takes a lot of time and due to the distance, there isn’t as much reliance upon the spring systems of the body as there is with shorter events (i.e., 5K). Therefore, in respect to training for an ultramarathon, with very limited ‘extra’ time, an individual must be able to prioritize what they will spend their time on. It is very likely that for an ultrarunner, prioritizing rest over strength training might be the right course of action while for a 5K or even a marathoner, this would likely not be the best approach.

Spring System

Within the body are a series of spring systems, most notably the Achilles tendon. While it would be easy to pass off tendons as not much more than rubber bands that hold the body together, from a performance standpoint (specifically in regard to running), they can be trained to increase performance – just like muscles. Let’s go back to the rubber band analogy for a minute. Let’s say that you have two rubber bands; both are the same length but one is quite stretchy while the other is well… not as ‘stretchy.’ Now pull back each one the same distance and let it go. Which one will go farther? Right… the tighter, less stretchy one will travel farther.

Applying this analogy to the Achilles tendon, the stiffer it is, the more energy will be stored and released, thus increasing the efficiency of a runner. While the Achilles tendon will stiffen solely through running, it can also be enhanced via strength training to optimize running performance.

Overall Fitness

Regardless of any running-specific advantage or perceived disadvantage, strength training should also be viewed through the lens of overall health and fitness. There are a multitude of health benefits, not to mention the aesthetic benefits that many endurance athletes want to achieve. Therefore, it is important to note that maintaining a strength training program while training for an endurance sport event does not have to specifically relate to running performance enhancement.

How Heavy?

To answer this question, an athlete must ask themselves why they are performing strength training. Repetition ranges should not be generically performed or assigned. Since we’re talking about endurance athletes, they are likely getting enough muscular endurance activity through their normal training (i.e., running, cycling, etc…). Therefore, assuming that an athlete has progressively adapted their muscle(s), the focus should be on gaining strength which correlates highest with high weight/low repetitions (3-10).

The rationale is this: If an endurance athlete is going to allocate time to strength training for the purpose of improving their performance, they should maximize their efficiency and time spent.

Single Dose (Per Week)

Ready for the great news? Research by Ronnestad et al., (8) has found that strength training just one day per week can maintain lean muscle mass and even increase power output.

What Order?

This is a very common question among endurance athletes – what order do I perform cardiovascular training or resistance training?

A study by Doma and Deakin looked to determine if either of the following scenarios was preferable (9):

- Strength-training session followed by running (six hours between training sessions)

- Running followed by strength training (six hours between training sessions)

What Doma and Deakin found was that in respect to running performance the day after the aforementioned training scenarios, the group that performed strength training prior to running showed greater running impairment (i.e., decreased running economy) versus the group that performed running followed by strength training.

How Long In Between Strength Sessions?

Perhaps the most relevant study in regard to integration of strength training was by Sporer and Wenger (2003). They looked at the effect of the duration of time between aerobic exercise and strength training (10). Sixteen male subjects were divided into two groups. One group performed high-intensity cycling intervals while the other group performed a steady-state sub maximal cycle test. The two groups performed an incline leg press (75 percent of 1-RM) at four, eight, and 24 hours after the cycle tests. Each strength-training assessment was done at least 72 hours after the previous assessment to ensure fatigue from the prior test was not a factor.

Researchers determined 24 hours is the approximate time for recovery in respect to being able to leg press the same repetitions as used in the control.

Subjects also performed the bench press post-aerobic assessments with no difference in repetitions. This confirms previous studies that showed the negative effects of concurrent training are limited to muscles used for both endurance and strength applications.

Range of Motion Specific

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve likely heard of the term, “Functional Training.” While this term has come to take on many different meanings, the gist of it is that training should be as specific as possible to the activity being trained for. In the case of strength training, this often means replicating movements and ranges of motion as closely as possible to the sport being trained for.

Here’s an example. Walk into any gym and you’ll likely find the leg extension machine to focus on the quads. Here’s the thing – while this machine might be applicable to bodybuilders who are focused on developing their quads for aesthetic purposes, unless you plan on high-kicking your way to the finish line of a 5K, it’s highly impractical and not sport-specific at all. So while front lunges and leg extensions both strengthen the quads, they do so in very different ways.

This is noted because while you might be able to rip off a 16 minute 5K, or lunge your way around the gym for 10 minutes at a time without being sore the next day, it might only take one set of 10 reps on the leg extension machine to render you useless the next day, aside from laying on the couch! So… when performing strength training exercises, be careful with which ones you’re doing and make sure they ‘make sense.’

Why?

Lastly, this is likely the the most important question to ask yourself. Why do you want to implement a strength training program or exercise(s)?

- Maybe you want to increase your power on the bike.

- Maybe you don’t care about increasing your endurance sport performance, but you want to do it purely for health reasons.

- Maybe you want to increase your running economy

- Maybe you want to focus on the aesthetic aspect

Whatever your reason, there isn’t a right or wrong answer. The main thing is to make sure that once you decide the reason or reasons for strength training, make sure that you’re focusing on the right things (ex: exercise selection, weight, repetitions, etc…).

Summary

The decision to, or not to integrate strength training into an endurance sports training program is very much an individual sort of thing. However, should it be integrated, building up slowly and focusing on proper form are the most important aspects. And like many other aspects of training, figuring out exactly the right dose, timing and weight is largely determined via trial and error. Lastly, if you don’t have any prior strength training experience, working with a strength coach or personal trainer that has a solid understanding of mechanics to assist with ensuring you have proper form is advised.

Brooks, G.A.; Fahey, T.D. & White, T.P. (1996). “Exercise Physiology: Human Bioenergetics and Its Applications”. Mayfield Publishing Co.

- DeLorme TL, Watkins AL.“Techniques of progressive resistance exercise”. Arch Phys Med.1948 ;29:263–273.

- Kraemer W.J., Gordon SE, Fleck SJ. Et al. “Endogenous anabolic hormonal and growth factor responses to heavy resistance exercise in males and females”. Int J Sports Med 1991; 12:228-35

- Hakkinen K. Pakarinen A. “Acute hormonal responses to two different fatiguing heavy-resistance protocols in male athletes.” J Appl Physiol 1993;74:882-7

- Kraemer W.J., Gordon SE, Fleck SJ. Et al. “Endogenous anabolic hormonal and growth factor responses to heavy resistance exercisein males and females”. Int J Sports Med 1991; 12:228-35

- R. C. Griggs, W. Kingston, R. F. Jozefowicz, B. E. Herr, G. Forbes, and D. Halliday. “Effect of testosterone on muscle mass and muscle protein synthesis”. Journal of Applied Physiology. January (1989) vol. 66 no. 1: 498-503

- Torjesen PA, Sandnes L (March 2004). “Serum testosterone in women as measured by an automated immunoassay and a RIA”.Clin. Chem. 50 (3): 678;

- Rønnestad, B., Hansen, E., and Raastad, T. (2010). “In-season strength maintenance training increases well-trained cyclists’ performance.” European Journal of Applied Physiology. 110(6): 1269-1282

- Doma K, Deakin GB. “The effects of strength training and endurance training order on running economy and performance.” Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2013 Jun;38(6):651-6. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2012-0362. Epub 2013 Jan 25.

- Sporer, B.C., & Wenger, H.A. 2003. “Effects of aerobic exercise on strength performance following various periods of recovery.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 17 (4): 638-44.

- Beattie, Kris; Lyons, Mark; Carson, Brian; Kenny, Ian. “The effect of strength training on body composition in distance runners.” 2015. Physical Education and Sport Sciences, University of Limerick. info:eu-repo/semantics/conferenceObject